Diary of a Maker | Part 1

Finding God in the Grain.

I was an artist and a maker as a kid.

I’d paint often, covering canvases and rendering album covers on jean jackets. Recreating Frank Frazetta’s iconic Flirting With Disaster album for the band, Molly Hatchet was my crowning glory. Along with a whole bunch of Dead, Boston’s legendary upside-down guitar spaceship, and U2’s photorealistic young boy’s face in black-and-white on the cover of War.

Sketches, doodles were a constant companion. My fingers were always working something into something. I’d make Franken-bikes out of spare parts from the junk yard, then construct ramps to launch them off of. Pretty much anything I could imagine, I’d try to make it. Even painted and renovated houses through my college summers.

The process of creation takes me somewhere. Always has. It opens a door to something simultaneously internal and primal, yet also expansive and universal.

Then something happened. I grew up.

And I’m not alone. Unless we’re intentional about it, it seems the older we get, the more we leave the physical act of making behind. We trade it for “knowledge-work.” Which has its own value. I found a grown-up, “status friendly” outlet in making books, brands, digital products and courses, media, content (oh how I hate that word), companies, events, and experiences.

But it’s different. Not the same as the physical act of making a physical thing. One that exists materially in the world. Born of body, sweat, love, hands, raw materials you can touch and feel. There’s a transmission that runs from your hands to your heart, and, not infrequently, brings tears along the way.

There’s something about the smell of fresh-cut wood, WD-40™, and danger that makes my heart sing.

Back in my NYC days, I realized I’d been missing being in physical maker mode. So I took a move to a new apartment as an opportunity to re-meet my maker-side. We gave away pretty much all of our furniture, so we needed a bunch of new tables. I decided to make them. Little did I know that table one, which would come to be known as the concrete behemoth, would end up six feet long and tip the scales at 150 pounds.

We started the hunt for parts online. My wife, Stephanie, found these amazing hand-crafted, powder-coated steel legs. We bought a pair of vibrant purple ones from an Artist, if I remember correctly, in Turkey. They arrived at our doorstep four days later. Amazing.

Now, what to do about the top? Stephanie and I talked about different ideas. Lacquer, oil, wax, paint, but we wanted to do something unique. What about concrete? Wouldn’t it be cool to give the top an artisanal troweled concrete feel? I’ve never worked with concrete before, but hey, how hard could it be?

Famous last words.

I went online and searched “how to make a concrete table top.” This led me, of course, to Youtube. There, I found a great DIY tutorial on making concrete counter tops and tables. Still this was pretty much all out winging it.

One of the best parts of making something from nothing, especially when you have no idea what you’re doing, is surrendering to where the thing is calling you to go.

That’s much more fun than just following a set of rules where you’re fairly certain of the outcome, but you also end up learning less and diminishing the possibility of genuine awe (read “catastrophe”) and surprise at the end of the process when you step back and say to yourself, “holy shit, it worked! I DID that!”

It’s a bit like creating your own recipes. You make awful, barely-edible concoctions and then something clicks, you get the mixture right and angels sing. The very fact you got so much wrong along the way is what makes the angel’s song so transcendent.

I think that’s why makers never stop experimenting. It’s the process, as much as what the process yields, that drops us into the playful pulse of the Universe where everything is simultaneously as it should be, while also rendering you into a joyful calamity of mayhem.

For me, tinkering is like a beeline to Source and Surrender.

Back to the concrete behemoth. What to do?

Much as I don’t like using the stuff, I had to revert to particle board. It’s heavy as hell and some particle boards can “off-gas” volatile compounds that aren’t all that healthy for you. In fairness to particle board, some people can do the same! I also knew the top would be sealed with 1/2 inch of concrete and I’d just have to seal the bottom with something else.

I ended up finding a 1 3/4 inch thick industrial particle board slab designed for warehouse packing tables. Three days and 125 pounds later, I swapped the new top on. With the steel legs, this thing now weighed in at around 140 pounds. And that’s before I poured and troweled three layers of concrete.

For the most part, I was enjoying working with my hands again, problem-solving and seeing something physical starting to emerge. Something I’d use every day. Something my family and friends would gather around for years to come. Something I could step back and think, “I made that.”

Why just “for the most part?”

Because the act of physical making isn’t my one thing these days. I was building in the middle of the total madness of a move and the larger gorgeous, yet complex mosaic of being a dad, husband and more than full-time entrepreneur, executive producer, product designer, educator, and writer. My mind doesn’t just drop into that special place where the world falls away and it’s just me and my craft. It takes time.

When physical making is your one thing, your profession or at least something you do in a substantial way every day, you build the space into your life that allows you to drop into the process in a different, immersive way that fugues time. When you’re making in the margins, though, you don’t. You can’t. You’re not there long enough, and your cognitive and emotional bandwidth is also somewhat, if not entirely, fragmented.

So your inability to fully honor the “ramping time” and preparatory rituals, coupled with the likelihood that you’ll get pulled out of the process prematurely can be stunningly frustrating. Once you’re ready to go, you just want to go. And stay there for a while. You want to get lost in the process.

Once you say yes to the experience of physical making, you want to be there long enough to find God in the grain.

It’s harder to get to this place once you’re a bit further into life and you’ve made the call to make on the side of the side of the side. Which, inevitably becomes not at all.

You can fight it. And I have. But reality always wins.

Truth is, for the right season, and the right reasons, that’s okay. A better approach is to own your choice and all that comes with it. Including the gift of having people around you who want so much for you to be a part of their experience that they keep asking for your presence. And you, theirs.

So you do the dance, knowing that on some random days you can drop deep into the maker zone, others you’ll stay surface-level and still others, you’ll bounce back and forth. If there’s a way, bring the people you love into the process.

Then, there is, of course, the nuclear maker-option. The one that finds you so called by your inner-maker that you decide to make making your life. You turn it into your one-thing. Or, at least your central thing, while demoting or delegating your former main thing to supporting cast level pursuits.

There’s actually a fantastic book about this called Shop Class as Soulcraft, about a rising star in knowledge-work finding salvation as a vintage motorcycle mechanic. I’ve been tempted in this direction more than once. And, truth is, my own 2x20 experiments are leading me powerfully back to this place. And, to sharing the experiences and processes along the way. I’m staying curious and following the call, we’ll see where it leads…though, in truth, I kind of already know. And longform Diary of a Maker entries like may well be a part of where it’s all leading. Along with my own rededication to the physical maker’s journey. More on that soon.

In any event, that’s why I used the qualifier “for the most part.” But there was also something else. I wanted to do right by my materials and those who’d enjoy what they turned into. You probably get that last part, but what about my materials? Why would I want to do right by my wood and concrete and water? Because there’s something inside of me that says, on some level, every resource is worthy of respect. Even inanimate tubs of concrete. Sounds weird, I know, but that’s just how I’m drawn.

This notion came roaring back to me in a conversation I had years later on the Good Life Project podcast with this stunning artist named Mike Han. He described his process of honoring and giving thanks for every element, every bit of raw material, he worked with, and the sacrifice that went into creating them.

Back to the table…again.

It’s make or break time. My concrete mentor, a/k/a the interwebs, tells me my ability to trowel the concrete in just the right way will make or break the whole project. I learn that the material will only be workable for about 20-minutes, so I have to move quickly. Did I mention I’m doing all of this in a relatively small NYC apartment? Doormen looked at me receiving supplies like I was nuts.

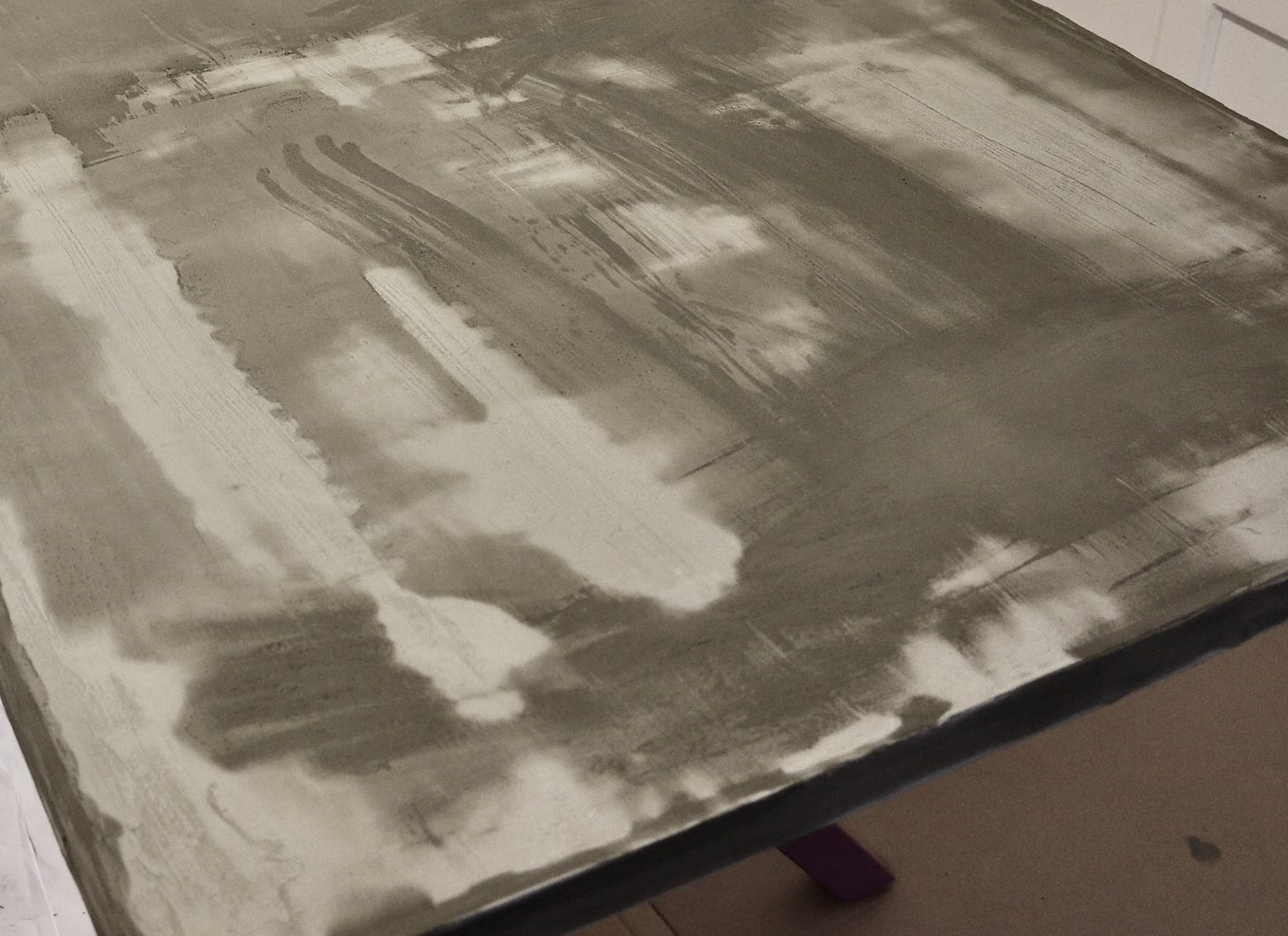

I mix up the first batch. It’s like a thick gray mud. I pour a long, oozing swath down the middle of the table begin to work it out toward the side. At a certain point, I get frustrated with the trowel so I reach down and use my fingers to spread the stuff around. I don’t realize my paw-marks will be so apparent—you can see them in the picture below—until the first layer dries and I see how much every movement shows.

At first, I think it looks like a big, fat mess. It looks terrible. But I know it’s just the first coat. And, more important, I also feel like a part of me, my imprint, is being layered into the table with every stroke, streak and roll.

Twenty-found hours later, I layer on the second coat. And that’s when the magic begins to happen. It starts to look like concrete. For the first time I start thinking I can pull it off. Create something that people can gather around. And make my people proud.

Still I notice my trowel work continues to leave all sorts of lines and patterns that will remain in the table.

I wonder how much I should leave in and how much I should sand out. Then I think more about what I like about things that are hand-made. And it’s not that they look store-bought.

I love it when you can see and feel the mark of the maker in the thing being made.

So, on the third and final coat, I try to make the marks more evenly spread and multi-faceted, more visually interesting, rather than just a series of long streaks and lines. But I also decide to keep them all visible and tactile, rather than sanding them out. You can run your hand over it and feel the areas of effort and ease.

I sand a bit, then let it all cure for another 72 hours. Then, armed with a thin, 6-inch roller, I layer on three coats of a special food-safe concrete sealer, then seal the bottom of the slab as well.

I’m a bit bummed once the sealer goes on, because I love the lighter color and grainy feel of the unsealed concrete and the sealer darkens and smooths the top. But, in the end, it still looked cool and, if I hadn’t sealed it, the porous nature of the concrete would have left it marked and stained within days.

Here’s the finished table…

Over the next few weeks, I find myself working with my wife and daughter to craft and resin-coat a kitchen table. And, over time, more tables have met some blend of their creation and/or demise, sometimes both at once, at my hands.

In case you hadn’t guessed, this isn’t really about building tables.

It’s about reconnecting to Self and Source through the physical process of making.

When we honor the primal desire to turn raw materials into something beautiful. When we strive not for perfection, but connection. Engagement. Absorption. Elevation. Creation. That deeply experiential and irreverent full-mind-body-massage that comes from breathing and thinking and sweating and toiling and working something into existence. Not just with your mind, but with your hands. It. Is. Magic.

I need more of that. And, if you’ve read this far, it’s a pretty safe bet, so do you.

Which is why I’m at a moment of reclamation. Bringing craftsmanship, creation, making, with raw materials, hands and tools, back into my days. And life.

And as I deepen into this journey, my plan is to offer more of these Diary of Maker™ entries as a regular part of the line-up here. To share the process, the dreams, the fumbles and stumbles, the evolution of ideas, skills and vision, the experience of losing yourself in the process of full-body, full-contact creation. To bring you into the irreplaceable sense of immersion, sometimes ecstasy this level of devotion brings. It’s all about returning to who I’ve always known myself to be, sharing the experience, and hopefully, inviting you in, and inspiring you to do the same.

If you’ve enjoyed this, let me know in the comments. And, be sure to subscribe today, so you don’t miss the next juicy, and much more current, Diary of a Maker installment, which also happens to be the subject of one of my recent 2x20 experiments.

More journey, images and even video to come.

With a whole lotta love and gratitude,

Jonathan

Wake-Up Call #61 | The Call to Make

What do you do that makes you lose time in the best of ways?

How does it make you feel? Does working with physical materials give you a different feeling than creating in the digital or written word space?

What was the last project or experience that brought you to this place?

And, how to can you more of this, even just a few minutes a day?

Think on it, feel into it, walk with it. And, if you’re inclined, share in the comments.

I love this, and this resonates deeply, because it's how I feel when I do pottery. (And obviously, doing things purely for the love fo doing them is the subject of upcoming book!). I can't wait to read more.

Love this! Looking forward to more Diary of a Maker entries. I’m in the process of pivoting my career in design to focus solely on print design—tactile, tangible design you hold on to (literally and figuratively).